Speaker’s biographical notes:

Meeka Noelle Morgan, M.A., identifies with her Secwepemc and Nu-Chah-Nuulth heritage, and now resides in Secwepemc territory in the southern interior of BC. Both of her parents were sent to residential schools, but this was never spoken of openly in her home. Throughout her years at public school, she felt that the knowledge and history of her people was not acknowledged or explored adequately or in a meaningful way, which contributed to her feeling very invisible in the scheme of things.

Meeka studied the perspective of her parents’ generation on the impacts on families during the 1950’s and 60’s. She wanted to explore how the people in her community maintained their sense of family during this time, especially with the onslaught of residential school. Community and family members told their memories of family life before, during, and after residential school, and reflected on those impacts. Meeka wanted to keep the spirit of each person telling the story in the heart of her research, so she created a verbatim poetic narrative out of each interview, capturing the unique voice and imagery of each storyteller.

Learning Outcomes

Students will:

- organize details and information about material they have read, heard, or viewed using a variety of written or graphic forms.

- identify and explain connections between what they read, hear, and view and their personal ideas and beliefs.

- use information that they have read, heard, or viewed to develop creative works as response activities.

Steps to the Lesson

- Conduct a discussion on values and complete a Values Inventory.

- Complete a K-W-L strategy on residential schools.

- Watch a video narrative on residential schools.

- Write a poem reflecting on the residential school experience or student values.

- Reflect on the process.

CONNECT

Goals:

Students will

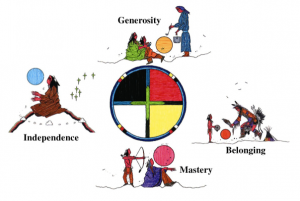

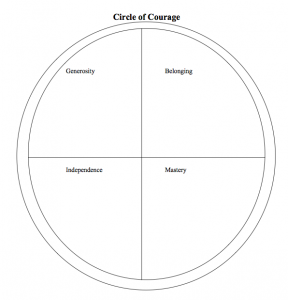

- identify their own values.

- view/listen to a video about one person’s childhood values and the impact of residential. school on those values.

- interview each other.

- create a poem about their partner’s values to share with the class.

Task:

Students will identify the impact of the residential school system on a family’s traditional values and create a poetic response by focusing on their own values.

Activate Prior Knowledge:

- Define values (beliefs of a person or social group in which they have an emotional investment). As a class, brainstorm examples. Use the following questions to guide discussion:

- How do you know the difference between right and wrong?

- What is important to you?

- Do different people have different ideas about what a ‘good’ person is?

- What does your family teach you about right and wrong?

- What things are important to your family?

- How does your family define a ‘good’ person?

- Do different families have different ideas about what a ‘good’ person is?

- Will your children have the same values as you do?

- Could anyone make you change these values?

- What are some ways people could take these values away from you or your children?

- Option: use the Values Inventory attached. Once students complete the values inventory, they meet with an A/B partner to compare their responses.

- Using a K-W-L strategy sheet, ask students to identify what they already know about the residential schools in Canada and the experience of aboriginal people in them.

Predict and Question:

Tell students that they will watch a video clip of a woman who wrote a poem about the way one of her community member’s values changed after going to residential school. Ask the students to predict ways that the person’s values were affected by the experience of residential school. What are they wondering about?

PROCESS

Video

Students will listen/watch the clip and use a Placemat strategy to aid comprehension. In small groups, the students create a common response to the video, recording words or images that they find significant. The teacher pauses the video at two key spots to allow students time for this process.

Videos

Click above to view video in Mac OSX (Quicktime)

(Video Length: 9 mins)

Click Here to Read Transcript

First, stop the video just after the speaker talks about restaurants and then talks about the way the grandparents were teachers: “my grandmother / clothed me / taught me the language / in my early life / teachers.” Allow students time to respond to what they have heard so far. Then, tell the students to resume sketching while they listen to Part Two.

Continue the video until the majority of the material about the residential school experience has played. The speaker talks about them being hungry and says, “after supper / we would run through those fields / pick whatever we could get stash them / in our shirt / make cache pits / for later.” Pause the video and repeat the above process.

Continue the video until the end of the poem, and allow students time to finish their placemat. Conduct a gallery walk so that students can see all the placemats that were created.

In A/B partners, students will compare the similarities and differences in the values described before residential school/during residential school and after the experience, using a Venn Diagram worksheet. Finally, students return to their K-W-L sheet, identifying what they learned about residential schools during this activity.

TRANSFORM

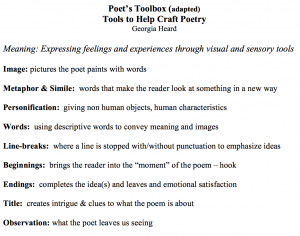

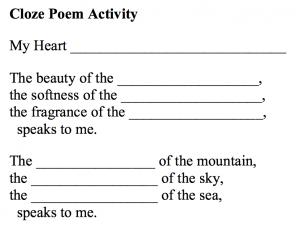

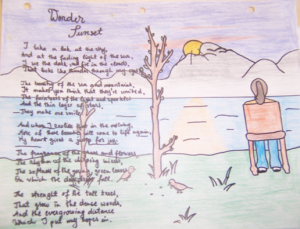

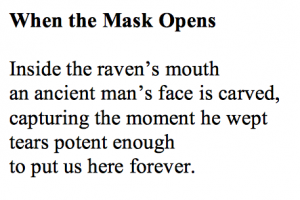

Option A: Students prepare a poem in response to the experience of listening to the narrative about residential school. This can be a free verse poem, expressing their emotions as they listened to the video. A sample poem, created by Meeka Morgan, represents her response to the difficulty for the people being interviewed, and is included.

Videos

Click above to view video in Mac OSX (Quicktime)

(Video Length: 1 min)

Click Here to Read Transcript

Option B: With the same or a different partner, students interview each other about their personal values. This activity asks them to return to an individual examination of values with a heightened awareness and broader understanding of their own values and the way they are influenced by society.

Students may either develop a list of questions to ask each other, or you may choose to use the initial brainstorming questions above. In either case, A/B partners ask each other questions, taking notes of their partner’s responses. The students will now have a greater sense of self when responding to the questions, and greater depth and an enhanced understanding should be evident in their responses.

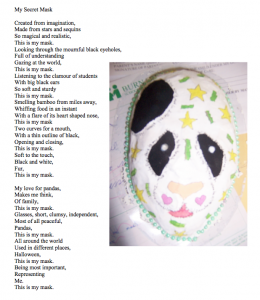

Finally, each student creates a “Found” poem based on the interview. Note: they are not using their own material: they are using their partner’s responses. Students create a poem (you may choose to require a minimum number of lines), choosing words and phrases from their interview notes that express the underlying values of their partner and the themes he/she revealed in the interview.

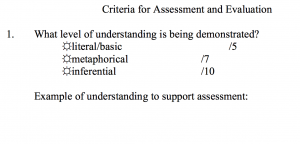

Students may have poetry readings in small groups or as a whole class. See a possible assessment rubric at the end of the lesson.

REFLECT

Students write a reflection about what they felt they did well in this activity and what they found difficult. They could also respond as to whether or not they feel their partner captured the essence of their interview in their found poem.

Extend learning or next lesson

- Use the video as part of a larger unit on residential schools in Canada.

- Use the lesson as part of a study of My Name is Sepeetza, by Shirley Sterling. \

- Students interview a family member or an elder in their community about how their childhood influenced their values, and whether or not those values changed over time. First, discuss what types of questions Meeka Morgan would have asked the people she was interviewing. Develop a list of questions together for the students to ask their guest. If possible, have the students take a photograph of the family member or elder to include when presenting the result of their interview (which could be in the form of an oral presentation or a short written report – if the written report is chosen, be sure to provide a copy to the person interviewed). This lesson is adapted from the assignment “Interview an Elder” in the above-mentioned novel study.